Why you need to pay attention to the UK Government’s long overdue new Critical Minerals Strategy.

The UK Government recently addressed an issue that has been urgent for some time now, by unveiling their first ever ‘Critical Minerals Strategy’.

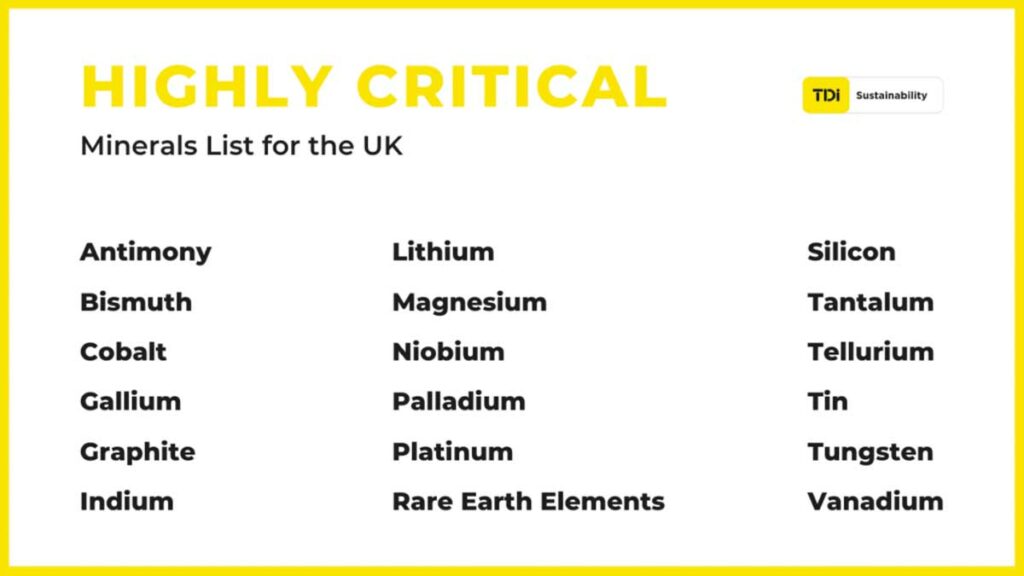

Announced on 22nd July 2022 and aimed at improving the resiliency and sustainability of the UK’s supply chains, the strategy emphasises how important minerals such as lithium, graphite, and silicon have become as key materials for the UK’s green transition and to support crucial markets.

A critical mineral is defined as a non-fuel mineral or mineral material essential to the economic or national security of the United Kingdom, which has a supply chain vulnerable to disruption.

The EU and USA both have critical minerals lists, and now the UK has one too.

Critical minerals were catapulted onto the political agenda when the so-called Dodd Frank Act was put in place in 2010. The Act threw into stark relief the vulnerability of these strategic minerals and, by so doing, their criticality, as well as the injustices surrounding the communities who mine them. It forced companies to participate in finding solutions to secure safe, reliable, and responsibly produced minerals for the products we all rely on.

Back then, the response of most Western businesses was simply to try and exit or avoid sourcing form those countries in fear of contravening the Dodd Frank Act.

But wherever there is a vacuum, it will be filled.

So, we watched on as massive investments were made by Russia and China to secure a plentiful supply for processing and converting these minerals into products.

We’ve been asleep.

The world is becoming steadily more dangerous according to the Global Peace Index, which announced the eleventh deterioration in peacefulness in the last fourteen years. And we’re only just now, in the midst of Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine, waking up to how fragile our supply chains have really become, scrambling to find a workable strategy that can provide long-term stability.

The EU speaks of aiming for ‘strategic autonomy’, but the stark reality is that most of the world’s minerals and metals are firmly in the hands of other countries’ businesses.

Our work at TDi Sustainability reveals that the battery, electronics, auto, solar, and infrastructure industries are all facing the same problem of over-dependency on unstable sources of critical minerals.

So, what is the solution?

The trending aspiration towards a circular economy where most of our critical mineral supply comes from recycling is definitely the ideal we should be working towards. However, we should not let faith conquer facts.

The reality is that we are at least two decades away from having sufficient secondary material in the system to reach the point at which we will make anything like a noticeable dent in raw material supply chains. In the meantime, we need enough minerals to get the green transition fully off the ground.

So the next ideal is that critical minerals supplies should come by developing resources closer to home. To which the key question is, are we willing to pay the additional costs that will inevitably result from higher salaries for workers and environmental controls at mega mines and industrial plants?

Witness the tensions in the EU over Ukraine – the biggest existential threat to the principle of liberal democracies – and the mood from business leaders is that they can’t wait for the war to end so that everyone can resume business as usual. Of course, ‘business as usual’ means lower-priced supplies through globalised supply chains, which simultaneously need to be ‘responsibly sourced’, free from conflict, environmentally benign, pro-democracy… Good luck with that!

While this mentality exists that we can have a resilient, responsible supply chain on the cheap, no progress will be made.

It’s time for the UK to invest in a multifaceted approach, and to be prepared to pay for it.

1. Invest in improving existing supply chains

First, we need to invest to secure and make more responsible the supply chains we already have. At TDi Sustainability, we help our clients do this by building enabling networks that make improvements at the very source of supply chains.

By channelling investment directly to miners and their communities through our work with the Fair Cobalt Alliance (FCA), in lithium and in gold mining (11% of gold goes into the electronics industry on which humanity is becoming increasingly dependent), our clients help turn hitherto controversial supply chains into resilient ones – developing fairer and safer incomes for communities who would otherwise be cast out of the ecosystem, and improving conditions on the ground to minimise environmental damage.

2. Kickstart the circular economy

Second, yes, we need to make supply chains more circular. Let’s examine what that means in practice.

Currently, a loophole in the Basel Convention allows signatory countries to export electronic waste abroad for ‘repairs’. But the reality is that the majority of our scrap metal is lugged abroad to Ghana, Nigeria, Brazil and other countries for people to sift through. Methods such as thermal processing or primitive acid-stripping are then used to extract key materials, which can produce deadly emissions. Work is underway to close this loophole, but it will take time.

In the meantime we need to get stuck in at the source of these scrap processors to improve matters on the ground. In Ghana we are working with local civil society to get to the root of the human rights issues in the dumps in Accra and find business-led solutions that can help bring a major source of scrap metal into the formal economy. This is an opaque part of our metal supply chain on which light must be cast to address the wrongs we are doing communities who work in these industries.

Ultimately, however, the shift to recycling nearer home needs to start now. For that to get off the ground we need to create incentives that will help change the economics. There are examples of companies pioneering this shift. One such is Redwood Materials in California, taking old batteries, defective battery cells and scrap material from their nearby Panasonic plant and turning them back into raw materials with, ‘no loss in effectiveness’. Redwood’s CEO, JB Straubel, estimates there may be a billion old devices containing recyclable battery minerals lying around US homes.

It’s time for us to get creative with the assets we already have, cutting down the carbon involved in transportation, ensuring processing standards remain high, protecting our supply through autonomy and reducing the need to mine materials in the long term.

3. Reposition the messaging

Third, we need to be prepared to pay a premium for metal and minerals that have been produced more sustainably, because if we want the UK to be sourcing responsibly there will be a higher cost. Through clear marketing and honest messaging, business needs to pioneer the way to ensure responsible producers can thrive.

The UK can be a leader in this. We have a strong industry in technical and strategy ESG services, TDi being one leading the way, but there are others. The UK is ahead of the game here, and it’s critical that we build on and maximise the advantages of this strong positioning.

4. Put policies in place

Fourth, we need sensible policies that incentivise responsible critical mineral resourcing. TDi have completed a project with the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) that outlines an approach to this that can set out a genuinely feasible road map. Our recommendations set out a path for how the UK Government could set a policy standard that can lead the way.

5. Explore alternative sources

Fifth, we need to consider potential brand new sources. One genuine option is to explore the mineral resources already available within Great Britain, those ‘pockets of mineral wealth from the Scottish Highlands to the tip of Cornwall’ that the Government’s new Strategy so proudly champions.

Another may be through deep sea minerals, for which we’ve recently undertaken extensive research for the World Economic Forum (available here) that sets out a vision for the next ten years of informed decision making. Environmentally, this route is highly opposed, and a moratorium is already being signed by companies against the use of deep sea minerals. But we also know that, behind the scenes, scenario planners are considering the options in case such a solution can ever be shown to be responsibly produced.

If we want to continue affordably owning the many things we now take for granted, we may have to boldly and honestly evaluate all sources of minerals. It’s an uncomfortable conversation, but we have to take the blinkers off and engage in fact-based dialogue.

Every week new reports emerge full of promise and hope about trendy techy solutions that may or may not have the potential to reduce our need for critical minerals in EV batteries and help us completely rethink what’s possible for the green transition.

Let’s celebrate and encourage each and every such development by inventive dreamers.

But in the meantime, let’s not forget that the World Bank has predicted that we need 450% more production to meet our technology targets for the green transition. It would be madness to turn our backs on the mineral supply chain. Not having a plan in place to secure the critical minerals that are currently essential to Plan A would be a grave mistake.

There are things we can do right now, today, that can secure more resilient and, yes, more sustainable, critical minerals supply chains for the UK. But we need to fully engage with the complexities we face and tackle them head on. This new Critical Minerals Strategy couldn’t be more timely, and the time for business to sit up and engage with it is now.