Why one of the hardest reports we’ve ever had to write is a call to action for businesses in the critical metals value chain…

One of the most difficult papers we’ve ever had to write at TDi Sustainability was published this week, and I wanted to take a moment to step back and share why this has been such a challenge.

The issues raised by the paper, which was written in partnership with the World Economic Forum, will affect all of us over the coming decade and beyond.

These are practical issues, calling into question our ability to meet COP26 targets, to make the technological transitions that are deemed essential if we’re to move beyond fossil fuel dependency, while meeting anti-poverty targets; and also, philosophical issues of equal stature, about how we, as a species, can come to agree on critical collective decisions for the common good, when current opinions are so polarised.

Our report was commissioned to be around twenty pages long but couldn’t be published under seventy. Deliberately impartial, as the World Economic Forum must be, Decision-Making on Deep-Sea Mineral Stewardship: A Supply Chain Perspective was created to unpack the intensely controversial discussions at the heart of the fierce debate on whether and how to extract deep seabed minerals. The recommendations made in the paper are primarily for private-sector businesses in the critical metals value chain today, as well as those who might well be in the future. But we hope the findings will be taken seriously by all stakeholders, including the governments striving to balance constituents’ needs through formulating policies for their own jurisdictions and those of the International Seabed Authority, environmental organisations and scientists that are fighting to protect precious species and ecosystems, communities relying on the Oceans for their living and those dependent on terrestrial mineral development, businesses developing the technology and plans to recover deep seabed minerals responsibly, mining companies currently producing critical minerals on land, and researchers examining the economics of metals supply, demand and circularity.

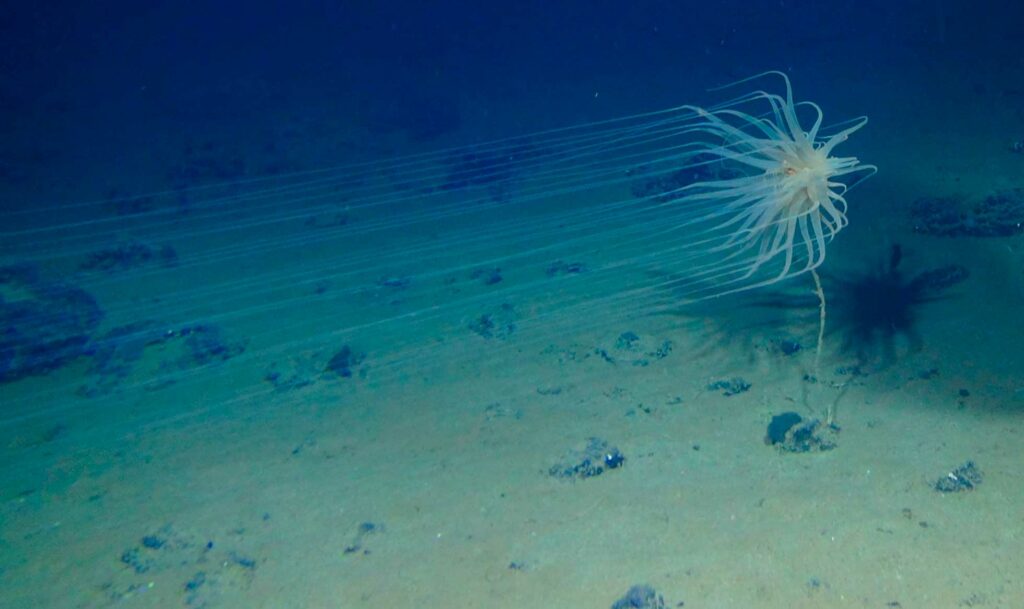

The case against extracting deep seabed minerals is that the invasive removal of sea-floor material, creation and disposal of sediment generated from machines used to extract minerals, and noise pollution in an area of the planet much of which is yet unexplored, could lead to untold species loss and disruption to precious ecosystems, with knock-on effects for biodiversity, coastal communities, and wider ecological impacts we can’t yet predict. With stark warnings form scientists about the impact that species loss and depletion of biodiversity can have on our lives, and its links to climate change, these arguments are valid and should be listened to very carefully.

Fauna including deep-sea corals attached to manganese crust on the Vogt Seamount in the western Pacific. Images courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas.

That mineral extraction will damage the ecology of the deep seabed in the mining zones is acknowledged by all sides of the debate.

The arguments in favour of pursuing the development of this apparently vast resource are also powered by environmental drivers.

As we move rapidly from an age of fossil fuels to an age of metals, in order to build the technology and infrastructure necessary to meet the Paris Agreement target of limiting the rise in mean global temperature to below 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, anxiety about metals shortages is rapidly rising. Since the invasion of Ukraine, with Russia accounting for 11% of the world’s nickel, prices of this important metal for electrical vehicle batteries have risen so dramatically as to cause the London Metal Exchange to be shut down amid fears of a melt-up.

This is a complex decision-making matrix. We face tough choices and the prospect of uncomfortable trade-offs.

It’s no wonder many decision-makers in the minerals value chain are cautious about getting involved in the debate at all, especially with other competing and more immediate issues to attend to in mineral supply chains. But get involved we must.

The painful truth to come out of our yearlong examination of this topic is the sheer extent of the gap dividing the two sides of the argument for and against deep seabed mineral development.

This is a gap that goes beyond moral opinion or geopolitics, it is also a literal gap in our global collective knowledge.

Our findings make it all too clear that we simply don’t yet have enough knowledge to weigh the benefits and costs and come to a clear point of view on whether there can be, and what would be, an acceptable balance.

(Relicanthus. Image courtesy of Craig Smith and Diva Amon, ABYSSLINE Project.)

It is a truism that more complete knowledge can lead to better decision-making, but it is also true that real-world decisions often take place in situations where knowledge is lacking or disputed, and where the outcomes of decisions are difficult to predict. It is also important to note that no party we spoke with claims they currently have sufficient knowledge to be able definitively to say that deep seabed minerals can be exploited responsibly. Rather, millions of dollars are being spent to gather and analyse the data needed for a more informed decision to be made.

In fact, there is more common ground on some fundamental principles than it may at first seem. Both sides of the debate acknowledge the need for more knowledge on all aspects of the potential effects of deep seabed mining, both positive and negative.

When talking about the stewardship of deep-sea minerals, organisations from across the spectrum of opinions use similar language and invoke the imperative for a ‘thorough understanding’ of deep seabed biology, taking a ‘precautionary approach’, ensuring the ‘protection of critical biodiversity’, and having a net benefit for the environment globally.

While the language used by these diverse organisations is often similar, however, there is no concrete consensus on its meaning, and this is where the greatest consensus gaps appear. There are no commonly agreed benchmarks on when risk assessments could be considered comprehensive, when research could be considered thorough, what implications local disturbance of the seabed may have on the health of the ocean more broadly, what environmental protections could be considered effective or precautionary, or how the requirements for each might vary between phases of operations. Achieving a broader consensus in these areas among others is crucial to give much-needed clarity on questions of knowledge sufficiency for decision-making on deep-sea mineral exploitation.

In the meantime, everyone already has an opinion.

These much-needed discussions become incredibly difficult because we’re all treading on political eggshells; debates become polarised so quickly.

The only way we will gain enough knowledge to move forward in time to make the best decisions for our planet and collective futures is if we get out of the boxing ring, come out from our opposing corners, and actually start talking with one another. And by talking, I mean listening and remaining curious about others’ points of view, before declaring our positions.

It’s okay to give ourselves time to think.

In fact, it’s the one chance we have to combine our power, fund joined-up research, and achieve a fully-rounded understanding of this exceptionally complex picture, so that that the best decisions can be made for the long-term wellbeing of our planet and communities.

It’s typical of our human nature that we only galvanise into practical action when things reach emergency status, but by that point it’s often too late to make informed decisions from an objective, consensually agreed perspective. The development of deep seabed minerals seems a long way off – but it’s really not that far away at all. Some observers say that commercial production could begin in 2028, if the rules being developed by the International Seabed Authority are agreed.

Should deep seabed extraction ultimately go ahead, private sector leaders in manufacturing and markets will have to make the decision on whether to accept these DSM minerals in their supply chains.

Now is the time for supply-chain leaders to be engaging in meaningful dialogue to understand the implications of potential future outcomes and formulate thoughtful policies.

All agree that such discussions need to be science-based and open to the possibility that extraction might not go ahead, but also that it might. My concern is that if we do not start bringing all concerned parties into these conversations now, even with the best intentions to make the right decision for the most people and for our environment, the debate could be less well-informed by a lack of rounded perspectives.

Abdicating from the debate now will not rout out the root causes of corporate reputation risk.

If you’re a supply chain manager reading this today, I challenge you to step beyond the fear of not-knowing, and therefore doing nothing, into the bravest position of all, which is to start admitting to not knowing, because it’s time we all got this conversation underway.

Here we stand with a chance to demonstrate true leadership and take comprehensive responsibility for the environmental and social outcomes associated with our metal usage choices. This includes their effects on societal goals for decarbonisation, the preservation of biodiversity and wilderness, the transition to a circular economy and poverty reduction. Unlike many other mineral supply chains we work on at TDi Sustainability, for which environmental and social issues have already surfaced, with deep seabed minerals we have a little time to engage, discuss and ponder the best way forward. This industry has not yet begun; it may never begin. But we need to start the conversation around our stewardship of deep seabed minerals now, because responsible sourcing starts with taking responsibility for the decisions of the future.